Selected project, the 2022 ZAMPA Award

Mauro Alonso Novak was born in 1925 in Lima (Peru). He is the youngest of two brothers, the son of a Polish mother named Elen Novak, and a Spanish father, Guillermo Alonso Prieto.

At the age of three his mother dies of a rare stomach disease and his father decides to leave. He embarks with his children on the “Buenos Aires”, an old steamboat, heading to Spain.

During the long voyage, the ship’s captain baptizes Mauro. A month and a half later they settle in Bilbao, the father’s hometown. Mauro and his older brother, Guillermo, quickly integrate into their new home. They live in Plaza Urizar and go to the Camacho Schools. Nearby there is a pediment where they begin to play Basque pelota. In the neighborhood, there were several gangs: Los Cavernícolas, Los Leales, Los Republicanos etc., but above all was Roberto, El Rey del Barrio. Roberto stole the bicycles belonging to the workers of the Altos Hornos de Baracaldo and gave them to needy children in the neighborhood.

On holidays they went to the cinema to see Russian films allowed by the Republic. A few years later his father falls ill and dies shortly after. The two brothers enter an orphanage in the city until the Spanish Civil War breaks out, and after refusing to take refuge in France they are transferred to an orphanage in Valencia. There they spend the war as they can, avoiding the intense bombardments from sea and air and basically eat rice and carob beans to survive.

At the end of the war in 1939, and taking advantage of the family rapprochement law that Franco allowed, Mauro and his older brother board a train to travel to Medina del Campo, in the province of Valladolid, where his uncle runs an agrarian farm. There his uncle sent his older brother to the city to learn English and leaves Mauro in charge of the pigs, relegating him to living in pigsties. A bad time begins for Mauro because the hard work together with the frost and the intense cold that he suffers living in the stables force him to look for a better future.

Mauro, already a teenager, enrolls in a team to work building dams and reservoirs for the Franco regime. For a few years he lives in improvised barracks in mountain areas building the current Spanish water resources. Finally they send him to rural Catalonia, where he participates in two major projects. A few months later he decides to settle in Barcelona. In the Catalan capital, in the midst of the post-war period, he begins working as a coal dealer until he falls ill with silicosis. The boss of the coal company sends him to the Tibidabo mountain to look for firewood because the coal is running out and the city demands fuel. It was then that Mauro, a country man, fell in love with the Sierra de Collserola. Years later he starts working as a stevedore in the port of Barcelona, where he loads the holds of ships with basic products bound for the Balearic Islands. Mauro lives in a boardinghouse on East Street in Chinatown for years. In 1976, without ever having had a work contract or any social security contribution, he is fired from his job at the port to be replaced by younger, stronger stevedores.

Mauro then begins to work as a night janitor at the pension in order to pay for his stay. Two years later, fed up with the grays (Armed Police), thieves and prostitutes, he decides to take his few belongings, some clothes and a blanket, to go live on the Tibidabo mountain. At first he sleeps in the open but shortly after he finds an abandoned hermitage and settles there. A few days later he meets a colleague who is in the same situation and welcomes him into his new home. They have a good relationship in general, but sometimes his new partner drinks too much. With the passing of the months the relationship is straining due to alcohol. One cold night while Mauro sleeps, his partner, totally drunk, decides to light a bonfire inside the hermitage, and falls asleep. An hour later and with difficulty breathing, Mauro wakes up and realizes that the hermitage is on fire. Without thinking twice, he grabs his partner by the arms and drags him outside, who remains asleep, or rather battered by the symptoms of alcohol. Mauro saves his life, but he loses his new home. After waiting for him to recover, Mauro picks up his belongings again and begins the search for a new place to live.

The weather is already cold, winter is upon him, and he must find a good place to shelter. The first days he spends again in the open, until one unpleasant morning, while he walks to get warm, he finds the mouth of a small abandoned mine, on the east side of the mountain, that is, on the sunny side. The entrance to the mine is hidden behind some bushes, it seems perfect for him. So he decides to go in and get comfortable in his new room.

As usually happens in autumn in Barcelona, it started to rain and didn’t stop for the whole week. The water poured into the mine, and the cold and humidity began to take their toll on Mauro. But it continues to rain and he has no choice but to wait. That night, while he slept wrapped in blankets and cardboard, a scolopendra bites his leg. Mauro would spend a couple of days with tremendous swelling in his leg and a high fever that would prevent him from leaving again in search of a better place. After recovering and gaining strength, Mauro begins the search again. For several weeks, he wanders through the hills north of the city of Barcelona. He sleeps under the trees and walks around looking for a new home during the day. An old house in ruins, close to the stately Avenida Tibidabo seemed ideal.

He settles there, on the ground floor, as he doubts the stability of the access stairs to the upper floor.

The next morning, he wakes up to the chirping of pigeons. Leaving the shack he meets a group of men who are hanging around the place. They tell him that they keep his carrier pigeons there, on the second floor. They belong to a pigeon fancier club in the Vall d’Hebron neighborhood. They allow him to live there and leave him in the care of his pigeons. Mauro spends the following months there, where from time to time, the “palomeros”, as he calls them, give him a small tip.

One day, after returning from the Sant Gervasi neighborhood to buy some food, he finds some of his landlords shooting bottles with their pistols. Mauro, traumatized by his childhood war, decides to leave that place without giving any kind of explanation. The forest welcomes him again. Days later, going down a narrow path towards the city, he came across a boy carrying two large jugs of water. Mauro gave him a hand and they walked together chatting until they reached a small valley on the side of the mountain, through which a stream passes, and in the distance a green meadow with three or four shacks and a fantastic orchard. The perfect place to settle. Mauro does not hesitate and builds a small wooden cabin, improvised with the remains of pallets and logs and branches of fallen trees. Mauro will live in that fantastic place, sharing his experiences with that pleasant community of neighbors and eating the fruits of a small garden that he worked rigorously for the next 12 years.

One humid and hot morning in August 1990, as he left his cabin, Mauro saw in the distance a delegation of gentlemen in suits accompanied by a group of workers walking slowly and talking. Mauro did not dare to ask what they were doing there.

Weeks later, also in the morning, huge bulldozers showed up and a few well-dressed gentlemen who visited shack by shack until they reached the last cabin. There, Mauro was waiting for them at the entrance. Those gentlemen explained to him that this area of the Collserola Natural Park had been reclassified and that in addition to building the Ronda de Dalt, the Barcelona ring road that would be built for the 1992 Olympic Games, they were also going to build a luxury development, even above the great public work. That meant that Mauro had to leave that place, and also he would be the only one who would not receive any financial compensation, since his cabin was not considered a home, it had neither bricks nor cement. The rest of his neighbors received 1 million pesetas to find another home, not Mauro, and that same day they tore down his cabin. During the following month, Mauro dedicated himself to raising the remains of his cabin up the mountain, to a place where he could live in peace. A place close to the Fabra Observatory, an astronomical observatory built in 1904 on top of a small hill very close to the maximum level of Tibidabo.

Nearby, a little above, passes the road with no exit, and little traffic, access to the observatory. Equipped with fire hydrants and small lanterns, perfect for accessing the area. The place is called “El Cedral” in honor of the species of tree that covers it. An ideal place: sunny side of the mountain, protected by large Cedars, strong and at the same time elastic, perfect for sheltering from the wind and snow. But it has a drawback, the place has a steep slope which makes it difficult to settle there.

It’s still summer and you can sleep in the open, but Mauro must hurry to build his new cabin before the first autumn rains arrive. The first thing is to dig a large terrace on that unevenness to be able to build on the plane. Mauro began to dig with enthusiasm in his new home. Days later, worn out by the hard work, he realized that after reaching a certain depth, the ground hardened remarkably. So he decided that he would make it long instead of wide, and three small cabins instead of one big one. The first one at one end, the most protected area, but at the same time the darkest, the dormitory cabin, the most urgent and important. The second, in the middle of the land gained from the slope, in a brighter place, the kitchen-pantry. Finally, he built a living room at the other end, the clearest and sunniest. A nice place to read and listen to the radio during the day, and see the stars and dream about astronaut stories at night. After the Americans’ first trip to the moon, Mauro became passionate about the conquest of space and began to read about galaxies and to observe stars and planets closest to Earth.

His recent interest in astronomy, his location and his sympathy, and perhaps some luck, led him to meet the astronomer in charge of the observatory. One sunny morning Mauro took the opportunity to hang the freshly washed sheets with rainwater heated in the sun in a large metal drum that he covered to increase the temperature of the water. After wringing them out, he lightly beat them in the wind and spread them out in the sun. By chance, the astronomer, while taking a break from cleaning the telescope, while enjoying a cup of coffee with milk while observing nature from the window, saw strange white spots moving behind the trees.

The scientist, moved by his insatiable thirst for knowledge, quickly left the observatory towards that place to find out what it was, that it moved, but it did not move. He went up the road from the observatory until he came to a road or firebreak where the power line runs that goes down steeply to the left, directly to Mauro’s house. She meets him face to face. At first they were both silent, but seconds later they introduced themselves amiably. The astronomer looked amazed, a few months ago there was nothing there. It was a small group of cedars, surrounded by pine trees and situated on a steep mountainside. A practically inaccessible place, and now, a small community of cabins avoided the slope in a long terrace. Mauro explained the reason for all that and they talked for hours. He told her that the place was not a coincidence. A cedral for your protection. The slope of the land and the distance from the city made it unusual. And forest, because it was all he had left. Then they talked about architecture, a great hobby of the astronomer and Mauro’s new occupation, since he was finishing his great work. He explained that he laid the foundation with a thick layer of gravel, which he had made himself, chipping slate with a large mallet. Then he stuck into the ground four large pieces of poles from the power lines, positioned vertically, like pillars. His previous experience had made him learn that if he uses treated wood so as not to be attacked by bugs, the construction resists much better in the middle of the forest. Then he placed some large wooden boards as a roof and these covered by thin aluminum sheets, on top of a layer of plastic cloth and finally all covered with branches and pinnace as thermal insulation and integration in the middle. The scientist was impressed by the execution of that project.

A few days later the astronomer invited Mauro to the observatory. It was a clear night, and he was able to show her some of the wonders of the Milky Way with a powerful telescope. Mauro was fascinated by all that. He had developed a good friendship with his closest neighbor.

Mauro finally finished the three cabins, before the rains and cold arrived. The next challenge for him was to get drinking water. He knew of a spring, that of Can Borní, the problem is that it was not close and the route was very hard with the water on our backs. Mauro collected only the water for drinking and cooking from there, the rest he collected from the rain. Food was harder to come by. He often went down to Barcelona to ask for food in the soup kitchens or in the parishes. But there they usually gave him cooked food, which you can’t keep, and it meant going into town every day. Some time later Mauro heard that the Red Cross and Caritas Diocesanas were distributing rice, flour, legumes and canned food to people in need and he contacted them. That was how he became independent from the city, since these organizations distributed food, hygiene products and some blankets at home through volunteers. Mauro seasoned his stews with plants, mushrooms and fruits that he collected in the forest. Garlic joints, wild asparagus, dandelions, nettles, rosemary, thyme, oregano, figs, wild plums and some well-known mushrooms and without risk of poisoning he could easily find them depending on the time of year.

At first Mauro lit a fire to cook, but he immediately realized the risk of doing it in the forest, especially on windy days. With the little savings he had, he bought a Camping Gas with a small propane bottle that he had to refill once a month. Taking advantage of the visit to the city, he would buy, at a flea market, some old western novel, if possible by his favorite author, by Zane Grey. During that winter he was insulating and perfecting his cabins to fight against the cold and humidity. He lined the interior walls of the bedroom with old blankets and cardboard and made some windows with some glass he had found. Thus during the day the sun entered through the windows generating heat and drying the humidity of the night, thus managing to illuminate the rooms to be able to read, cook or anything else. When summer came he would remove the windows to let the air flow and be cooler. In a hole dug in the ground he made a chest to keep food fresh for a few days.

One spring day, when he was on his way to Barcelona, and before going through the Barcelona Judicial School, in a house that had always been empty until now, he came across a fire brigade. They were opening and tidying up the station that served as a checkpoint in summer, designed to prevent forest fires. Mauro immediately struck up a conversation with them. One of them, the youngest, asked him if he made a fire to cook. Mauro told him no and explained that he had a Camping Gas, and that he also had a 500l drum full of water as a precaution. The young man then asked him where he got the water from. Mauro told her that he picked her up after the rain to shower and to wash clothes and kitchen utensils. He also drew drinking water from a spring, for drinking and cooking. The fireman immediately offered him a special key that opened the fire hydrants located on the observatory road, very close to his cabin. Mauro would no longer have to walk long distances carrying liters and liters, now he had access to running water.

That spring he also discovered a nearby stream that produced abundant water after the spring rains. The years passed and Mauro was more and more adapted to that forest, he was happy living there.

He lived with a small mouse and a couple of robins that came to peck at his kitchen. In addition, a late-night horsewoman and a group of gluttonous wild boars often visited him, the latter climbing onto the roof of his bedroom and causing great destruction at midnight. He also fed a group of pigeons every morning and a hungry hawk that swooped down on them, starring in documentary scenes before Mauro’s eyes.

The hoopoe and the blackbird are the noisy neighbors who alert their family to the presence of Mauro. Also a lost dog finally decided to stay and live there for a while. An infusion of thyme and toast with oil and salt start the day. Making the bed, cleaning the cabin, washing some clothes while the sun is shining and finally fixing and reinforcing the protective fence of the orchard that the wild boars have destroyed. So Mauro decides to go down to the city to get some food, since the pantry is empty. In Barcelona he visits the Caritas facilities to see if they can provide him with some food. Upon returning to the forest, he sees from afar a patrol of the National Police that is hanging around his cabin. Mauro quickly approaches them, frightened, thinking about the possibility of being kicked out of there. The agent tells him that they are taking a census of the people who live in the forests of the Sierra de Collserola. The National Police officer in charge of security at the Judicial School, and a friend of Mauro’s, had told them about him. The policeman asked him if he was Spanish. After Mauro’s statement, the agent explained that he had the right to receive the minimum non-contributory pension. He also told her that he would help her process it. A few days later, Mauro went through the Sarria Social Security office, where he had to sign the documentation that the kind police officer had processed for him.

Not having an address in the neighborhood, Mauro registers at a bank branch where from now on he would receive his pension every month. That was a great relief because he would never again have to ask for help to eat. Now every day he took a walk to the town of Vallvidrera to buy bread and other food, chat with his people and become a neighbor of the town.

Reading, studying, listening to the radio, going for a walk, getting to know new places, exercising and many more, became important things for Mauro. He bought a small transistor to listen to the Athletic Bilbao and Barça matches, a guide to stargazing, binoculars, good boots and a heater that adapts to the gas camping for cold winter nights. Later he was also able to buy some glasses that would be of great help and an old watch at a flea market. In 2004, when he was fulfilling a photographic assignment on real estate speculation for a publication, and having to illustrate the appropriation of public land, I began to look for people who lived in shacks. I visited the Besos y Llobregat river basin, where shacks abound. But none of them were inhabited, they were only used on weekends for family barbecues or growing vegetables in the garden. That day, while I was driving from one place to another, I heard a news item on the radio that spoke of people without resources who lived in the forest. I started to investigate and it became clear to me that I had to find one of these people to illustrate my story. I traveled a different route through the mountains of the sierra every day of the week, but I did not find any person who lived in the forest. There were homeless people who slept in the mountains but did not live there. They came to spend the night fed up with wine and with four cartons for the cold.

The last day, when I was coming down from the Tibidabo mountain and heading home, as I passed near the observatory, I saw a person refilling water jugs from a fire hydrant. I watched him from afar for a while. Finally I decided to follow him respecting a certain distance. After a while, descending a steep path through dense vegetation, he came to a cabin. I followed him and got closer. Arriving at the first of the three cabins, small and open on one side, I found him sitting in a chair flipping through a free newspaper he had picked up from the bakery.

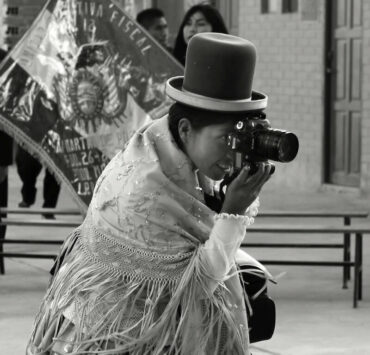

I introduced myself right away, because I felt like an intruder in someone else’s house. He immediately made me feel at home, offered me an infusion. We talked throughout the afternoon. Before I went back home, he invited me to listen to a football game together the next day. I gladly accepted. I visited him, and we shared pleasant moments for several days. One day, while we were having breakfast together, I explained my project to him and asked his permission to take pictures of it. Mauro agreed without thinking twice. From then on I started visiting daily, and he began to share his life with me. He always carried the camera with him and photographed everything he did. He would show me places, plants, animals, he would tell me stories and we would talk about all kinds of things. We became good friends. A few years later, he met my wife, Clara, and saw the birth of my two children: Pablo and Miguel. One hot afternoon in August 2008, Mauro saw a group of wild boars arrive, like every day, two females accompanied by their respective scratches. He came out with some stale bread from the kitchen, and then he saw that there were two more guests, a big male and his sentinel. Mauro did not give it much importance, but when he was distributing the bread, there was a brawl between them, with bad luck that in a great attack from the male to a female, he was caught in the middle. The big wild boar hooked Mauro behind the thigh of his left leg and took him with a prick a few meters, thus tearing his leg. In the end he fell to the ground. He got up immediately but it didn’t take long for blood to trickle down his calf, thus flooding his shoe. Mauro lost a lot of blood. He went to his hut and got a piece of cloth. He tied it tightly around her upper thigh like a tourniquet. Mauro was losing a lot of blood and felt weak and dizzy. He lay down on the bed, tightened the tourniquet, and after a while he lost consciousness.

The next morning Mauro was woken up by a retired resident of Vallvidrera, who had come over warned by the baker. Mauro had not gone to buy bread and he always did. When he looked out the door of his cabin and saw all that blood everywhere, he ran to the fire station. A few minutes later, a fire brigade patrol urgently evacuated him to the Vall d’Hebron Hospital. Mauro was operated upon by the surprise of the surgeon due to the wound caused by a wild boar. The sciatic nerve affected him, which together with his age of 83 years, would make Mauro never walk like before again. A month later he was discharged from the hospital, but he could not go back to living in the forest, his leg did not respond to him. Mauro would enter a private residence for dependent elderly people in the center of the city, and paid for by the Administration since public residences are overflowing. The mental state of the elderly hospitalized there was very bad, and Mauro could not have a conversation with any inmate, only with the staff, mostly nurses of South American origin. Through the window, protected with metallic threads so that nobody falls down, he only saw buildings, concrete and asphalt. Mauro did not want to continue living. Two months after his accident, and after my wife’s insistence with the Public Administration to find an 83-year-old person, who is not a relative, who has no family, and who has been living in the forest for the last 30 years , we find Mauro in the private residence for the elderly in the center of Barcelona. Mauro told us everything in detail, and he also told us that living like this was not living. We feared the worst. Clara, my wife, looked, asked and moved, until she found a solution. A few weeks later Mauro was accepted into a fantastic home for the elderly on his mountain.

The sisters of San Vicente del Paul accepted Mauro, as one more resident of the town, at the Betania Residence on Mont Dorça de Vallvidrera street.

A wonderful place and with his neighbors in the same situation with whom to share this sudden final stretch of his life. Also thanking the affectionate and professional treatment of the sisters, they were so different from the previous ones, and that was what an elderly layman of the Republic told you. Mauro would stay in that beautiful modernist building from 1908, which was the Hotel Buenos Aires, until 2012. The Betania Residence moved to the new facilities in the garden area of María Reina on the Vallvidrera road.

Mauro dies at dawn on Saturday, September 18, 2021.

About Daniel Loewe:

In 1980 his family moved to Barcelona. Graduated in Photography in the first class of the UPC (Polytechnic University of Catalonia) in 1997, his relationship with the world of images began in the photography shop that his father had. At the age of seven he is given his first camera as a gift.

He started working as a freelance photojournalist for different media and agencies. Currently he combines architecture and landscape photography with documentary with his own long-term projects. Awards: “Premi Comunicació i Benestar Social” Press category, Barcelona City Council (1999), EuroPress Photo Awards Fujifilm Europe category (2005), Anuaria Award Photography and Design category (2007), Letra Award Visual and Graphic Communication category (2007), European Design Awards (2008), iF Awards Communication Award category with the photos of the book “Pez de Plata Barcelona” by Editorial Actar (2010). Nominated for the Oskar Barnack Award 2022. Finalist ista Zampa I I Héctor Zampagl ione Photojournalism Award 2022.

Daniel Loewe is a member of UPIFC and Photographic Social Vision and lives in Barcelona where he works as a photographer.

Websites: